Originally, Mario was a normal sized man fighting monstrous turtles who stood as tall as him when on all fours. He evened the odds by becoming “Super Mario”, a giant who could go toe to toe with these adverseries and break ceilings using only a single raised fist (and possibly his cranium depending on how he was drawn).

However when Super Mario Bros 3 came out in Japan, something changed in the canonical artwork. There was no longer any distinction between Mario and Super Mario in the instruction manual's illustrations other than the scale of the images. When “Super Mario” put on a suit, he was drawn like a normal sized, pudgy man. All of the cartoons, comics and other merchandise reflected this by showing only one size of Mario. The “tiny” version went unseen except in the games themselves.

![]()

Shortly after that Super Mario Bros 2 was released in America. As everyone knows, this game was different from the Japanese SMB2 and was actually a modified version of the previously unrelated game Doki Doki Panic with the main characters changed to be Mario and his associates. As a hold over from the source game, Mario had a life bar that always started at two. As a nod to the past titles Mario shrank to a tinier version of himself with a huge head when his life bar dropped to one. However this small version was somewaht silly looking and featured an enormous head on a tiny body. This was probably done so that the game could still believably force players to duck to avoid certain obstacles.

The order had been totally reversed: now Mario was a normal sized man who, when struck or hurt, became a little person, sometimes with a huge head. Or as my nephew refers to it, a baby. This is now firmly cemented as the way things work in the Mario universe; in the opening cinematic of New Super Mario Bros Wii Mario arrives at a party at his full size but regresses into a dwarf after being struck by a flying object.

The best proof that the concept of a “Super” Mario had dissappeared was a picture from the instruction manual of 2011's Super Mario 3D Land which officially refers to the two versions as “Normal Mario” and “Small Mario.” Adding insult to injury, “Small Mario” also loses his hat in this game, as if to suggest short people have no reason to live wear hats. I think they should've also made him bald. The picture below compares the original Super Mario Bros's hierarchy of Mario states to the one created for Super Mario 3D Land.

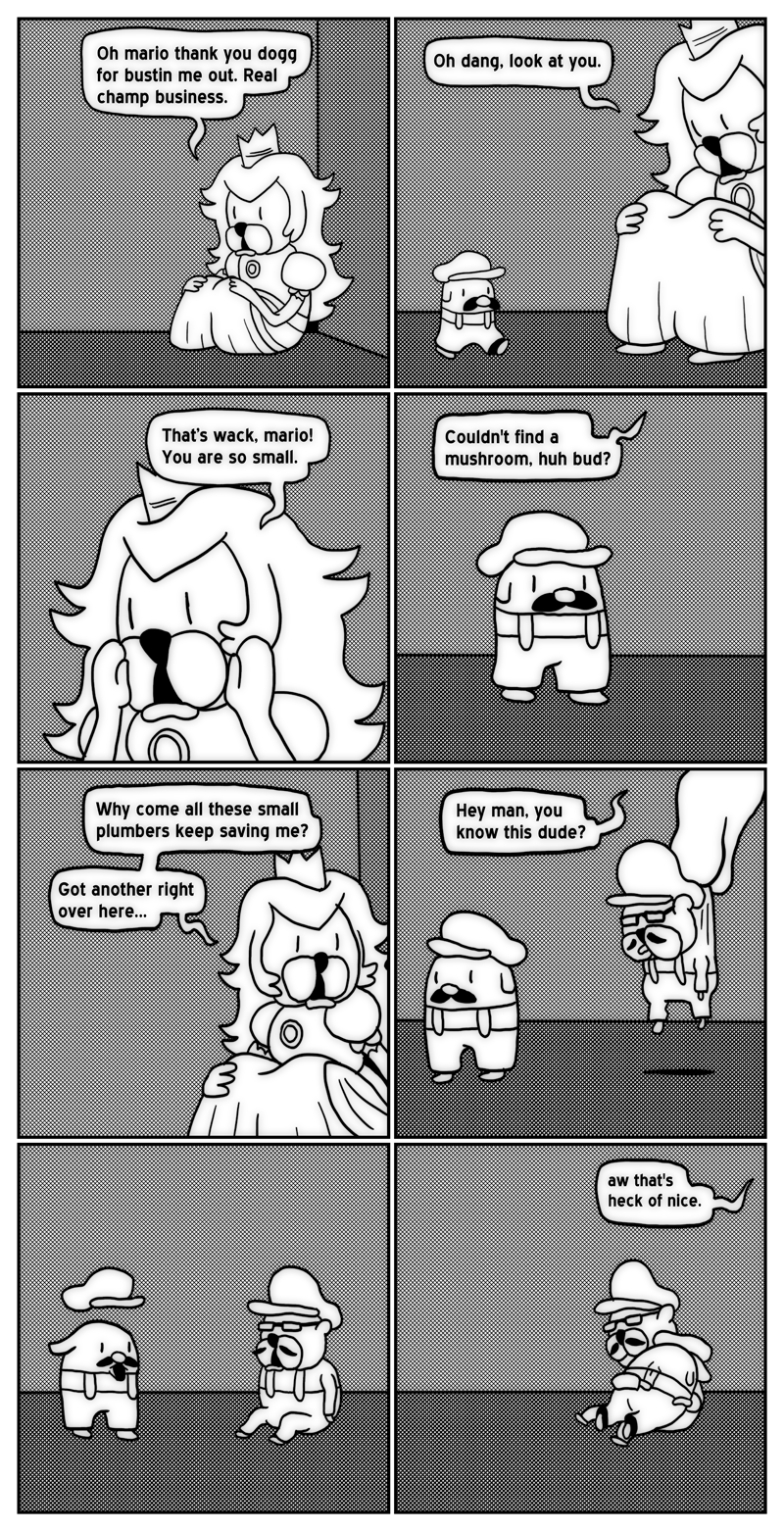

What's stranger is the Princess, aside from her apperance in SMB2, is portrayed as always being a consistent size. This comic by KC Green from USgamer focuses on this disturbing phenomenon.

This all begs the question: is Mario's original size the bigger one, which he only reattains after eatting a mushroom, and does his smaller version represent some terrible affliction or curse? Or is the smaller Mario his true self, which he hides from even those closest to him by eatting magical fungi before attending his numerous cake themed galas?

Eating a mushroom to become a giant is empowering; but being turned into a vunerable semi-deformed version of oneself when being critically injured is weird and kind of depressing.

I'll always appreciate the original, rougher version, where Mario- who is no more than a squat little fat guy- grows into a titan to battle the forces of evil.

The ending of the 1994 Donkey Kong for Gameboy, despite being released well after SMB3, celeberates the original theme behind the mechanic. After defeating Donkey Kong, Mario's girlfriend Paulina, finds a magic mushroom which she offers as a gift. In this game Mario is always “small”, but is redrawn so that he looks more like a normal person instead of the “big head” style from SMB2, so when he powers up in the ending he seems to the player to have actually grown to a somewhat shockingly large size (he also loses most of his ponch) so it makes sense that he then proceeds to pick up the villianous Donkey Kong and hold him triumphantly over his head. Donkey Kong's son then runs after Mario implying they will fight; this is a reference to the sequel to the original arcade Donkey Kong, Donkey Kong Jr, which featured Mario playing a villian who had imprisoned the great ape (I am unsure why God never answered my prayers that such a sequel be made).

According to this article from Slate, Gorillas are “approximately six to 15 times as strong” as humans and any Gorilla that was not incapacitated by illness or drugs would be capable of savagely tearing the arms off of even the world's toughest human being in a matter of seconds were they to engage in an all-out brawl. Given this scientific fact, it makes sense that when Mario touches Donkey Kong in the Gameboy game the ape picks him up, shakes him violently, and then throws him to his death (the implication being that Mario's neck has snapped in the process). So clearly this is scientific proof that the large Mario seen in Donkey Kong's ending is indeed the “Super Mario” from the first Mario Bros who possesses extraordinary strength surprassing that of a normal human.

I also want to comment on some uncomfortable Freudian elements that may be at play in the ending. It is heavily implied that Donkey Kong ‘94 takes place before the events of the first Super Mario Bros. Mario has just traversed the world to rescue his girlfriend from a giant ape, yet here she is apropos of nothing in this, their first moment of safety and calm following what would have been a tramautic crisis, suggesting some exotic enhancement drug to Mario as if to say he wasn’t good enough for her already. This scene may show an important moment in Mario's personal history, where feelings of rejection by his far more attractive girlfriend caused him to start hiding his normal size from others by pretending his “super” size was in fact his normal stature. These same feelings of inadequacy might have also sparked Mario's subsequent promiscous behavior, where he actively sought to cheat on Paulina by seeking out relationships with multiple princesses perhaps in an effort to prove his masculinity to others.

But I digress.

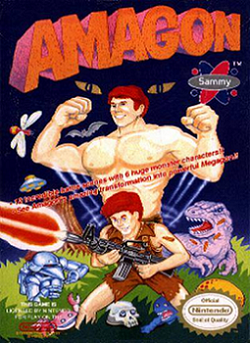

A few other games have the original version of the “average person becomes big person” trope, but the one that does it best is the 1989 NES Platformer “Amagon”. Amagon tells the touching story of a weak girly man named Amagon who travels the wild jungles and is frequently murdered by birds or spiders. Amagon's only real hope is to collect a power up which transforms him into Super Amagon, a muscular, hulking version of himself capable of obliterating any birds or spiders that cross his path with a single blow of his mighty fists. Though Amagon isn't a great game, I appreciate how it most better represents the original theme of the “Super Mario” mechanic by putting the focus on Super Amagon being powerful instead of regular Amagon being weak. Normal Amagon, though he does look skinny and dies after one hit, is not drawn in the “super deformed” style of later iterations of “small” Mario. He also uses a gun to fight. Super Amagon however relies on close range physical attacks and has a real life bar. Because Super Amagon is able to sustain damage and survive, the player feels a sense of relief everytime they make it far enough to transform. The game becomes all about managing to survive as normal Amagon while waiting to transform or managing the resources to stay as Super Amagon as long as possible.

It's worth noting that the idea of “normal man becomes empowered by eating thing” was a key element of Popeye, who gains his super human abilities after eating spinach. Mario's creator Shigeru Miyamoto originally intended for the first Mario game, Donkey Kong, to be a Pop-Eye game instead. When negotiations fell through Miyamoto created Mario to stand in for Popeye, Donkey Kong to replace Bruno, and the slim Paulina to replace Olive Oil. However there was no real power up in the original Donkey Kong, aside from a mallet item that could be used temporarily. It wasn't until Super Mario Bros was released five years later that the character of “Super” Mario became tied to a premise that strongly resembled Popeye's most memorable element.